Last year I became really inspired to try and emulate a more period texture and look for my banner works. One big allure of this was getting to work with gold leaf! I had come across some examples of standards that were not only painted, but gilded also (See examples below), giving extra sheen to the surface and creating a sumptuous aesthetic that I really want to emulate.

I did a couple of small leafing tests to see what look it would achieve, how it compared to simple colour on silk, its flexibility and wear.

What I found is that it was fairly easy to apply, the sheen it gave is fantastic and it is so fine and thin that the flexibility of the silk was not terribly affected by the gold, although it does retain fold marks if stored folded.

Upon looking for more references in the British Library collection, I came across this illumination by Jean de Wavrin from Anciennes et nouvelles chroniques d'Angleterre, volume 1 Netherlands, S. (Bruges), 1471-1483, that depicts

a knight with a standard with gold lettering. Not only did this supply another reference for gold lettering on standards of the period, but there also appears to be distinct lines in the standard, that look fairly evenly spaced and could indicate that the media used to paint the banner affected the canvas or silk to retain heavy creases after being folded.

| |

| Detail fromAnciennes et nouvelles chroniques d'Angleterre

Jean de Wavrin, 1471-1483 Bruges

Illumination

British Library

http://www.bl.uk/catalogues/illuminatedmanuscripts

|

|

Battle standard of the Ghent civic militia emblazoned with

the Maid of Ghent

Agnes vanden Bossche (attributed to), 1482 Bruges

9 x 3ft

Linen canvas, painted, silver leaf, silk fringe

Ghent City Museum, Ghent, Inventory Number 787

http://www.stamgent.be |

|

| Banner of the Guard, Spoils of the Battle of Nancy 1474-76, Burgundy Silk taffeta, gold, painted (unknown composition), applied silk fringe 342 x 113cm |

My first attempt was a anachronistic version of an ecclesiastic vexillum depicting St. Thaddeus. I painted this in the modern dying method and then used modern gilding size to apply the gold leaf to the lettering around the border of the piece, as well as a diadem on St. Thaddeus.

| ||||

| Silk dye, gold leaf, Approx. 80 x 100cm, Completed 2014 |

Notes: I was very happy with the way this piece came out. The colours came out beautifully and the gold is just aesthetically awesome. It supports the desired aesthetic enormously, however I realised after seeing it flying that the fine silk becomes slightly translucent. I'm not terribly happy with that as it affects the impact of the colour and makes the detail of the design less visible.

I attempted to create a fringe on the outside edges of the banner by fraying the dyed edges. This took some time and although it did create a lightweight fringing, again, it is not as full as the extant examples that are girt with adhered silk fringing.

Ursula's Guidon

My next project was a banner as a gift for a friend who was being elevated into the Order of the Laurel. For this project she supplied 3 meters of silk taffeta. I hunted for silk fringing, but had to settle for poly fringing, dying segments in order to get the alternating stripes that were common in Burgundian standards.

This banner loosely referenced the design features of a Burgundian Guidon (1474-76, Charles the Bold style. i.e. asymmetric triangular shape, single tail finish at 1m high x 3m in length) in order to make a beautiful statement piece that could carry her motto. As seen in the example above, the lettering of their standards was sometimes applied with gold leaf. Remnants of silver leaf also appear on the lion in the Maid of Ghent standard. (1482) Rather than making an exact copy, I have kept as close as possible with texture of the material and included her badge and device, replacing the saint and motto of the extant Burgundian examples.

|

| Silk Taffeta, gold leaf, acrylic, applied fringe. 3x1m, Completed 2015 |

|

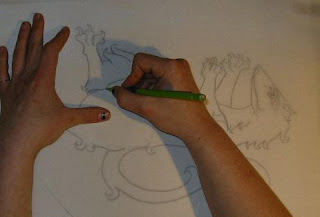

| Detail during construction |

Notes: The

gold on silk taffeta really popped! The gold leaf does not affect the

flexibility of the silk very much, which means the piece still retains a

beautiful lightness. The richness of colour is very effective.

Notes: The

gold on silk taffeta really popped! The gold leaf does not affect the

flexibility of the silk very much, which means the piece still retains a

beautiful lightness. The richness of colour is very effective.I used acrylic paint for the black details. This is a modern compromise for the egg tempera or oil paints that were used in period banner production. I utilised this media for a couple of reasons. Firstly, because, I only had a few weeks to finish this project. The gold leaf took a lot of time to apply and it takes a day at a time for the gilding size to dry. So by the time I got to painting detail I did not have enough time for oil paints to dry completely, as it can take days at a time for oils to set, especially if the weather not conducive to the drying process. Secondly, as previously stated, I am interested in recreating the aesthetic of extant banner design, rather than experimenting with the chemistry of period artworks. (As this is a massive rabbit hole that I would get lost in and possibly never resurface.)

The choice of media looks very effective, but results in a heavier banner than the modern resist method, which means it does not fly on a breeze.

This is not terribly important, but it is something that I like my standards to achieve, because it is a more satisfying finish. We expect a flag to fly in the breeze, but this standard would have to have a gale wind or be flown from a fast moving horse in order to see it fly.

The choice of media looks very effective, but results in a heavier banner than the modern resist method, which means it does not fly on a breeze.

This is not terribly important, but it is something that I like my standards to achieve, because it is a more satisfying finish. We expect a flag to fly in the breeze, but this standard would have to have a gale wind or be flown from a fast moving horse in order to see it fly.I had used gold leaf on a couple of other small projects and found that there was a step used by period painters that I had missed and has created an issue that needed solving. I hadn't been varnishing my gold! After taking my banners to long, wet events, leaving them out through rain and shine, some of the gold has begun to tarnish. I hadn't thought to varnish until this point because I have been using imitation gold leaf and had not thought it would react to moisture in this way.

|

| Tarnished gold |

"... But you must (varnish them) afterward; because sometimes these banners, which are made for churches, get carried outdoors in the rain; and therefore you must take care to get a good clear varnish..."

- Cennino d’Andrea Cennini,‘Il Libro dell’ Arte’ (The Craftsman’s Handbook) Translated by Daniel V. Thompson Jr, Pg.104

So in light of this, I decided to do a small test piece to test the flexibility, weight and finish of both varnished gold and oil paint on silk on both sides, following Cennini's methods of stretching and applying a thin layer of gesso to prime the silk on both sides, then scraping it down to a fine, smooth surface before applying paint, gold then finally varnishing the gold.

Notes: The results of this experiment conformed a couple of theories I've had for a while. The texture that the oil paint provided was not dissimilar to that which I was achieving with acrylic. However it did take as long as 4 days for a layer of oil to dry. The oil paints left some brush strokes, which would not give a desired look to compliment the very flat style of 15th century pieces. Perhaps a thinning medium would assist, but that is one downfall of modern oils.

The

quality of colour the oils supplied was very nice and the quality paint

provided a good coverage with less need for time consuming repeat coats

which are described as the process used to paint in egg tempera. Egg tempera being the predominant method used of painted banners before the

introduction of oil paints in the 15th century.

The

quality of colour the oils supplied was very nice and the quality paint

provided a good coverage with less need for time consuming repeat coats

which are described as the process used to paint in egg tempera. Egg tempera being the predominant method used of painted banners before the

introduction of oil paints in the 15th century.The finish of the piece was slightly rigid, but not unmovable. It retained creases and I believe on a full scale piece would be quite heavy on the silk.

The varnished gold was slightly more rigid than before varnishing, but its texture was very similar to the painted section. No cracking is apparent on the piece after much folding and playing. This could be due to the varnish coat being only very fine.

One surprise bonus to following Cennini's instructions of prepping and priming the silk for gilding was that the finish of the gold on this test is much smoother than my previous attempts. The banners I have been gilding have had the gold applied directly to the silk. This method worked fine, but the texture of the fabric was visible through the gold, as the leaf conformed to the texture of the fabric. When priming the silk with gesso and scraping it back to a flat surface, you clog the openings between the fibers of the silk, leaving a perfectly smooth carrier for the gold leaf, the result of which is a perfectly smooth gold coating with even higher sheen. Very exciting!